Introduction to Ediscovery

The discovery phase of litigation is a crucial pre-trial process where parties exchange information and evidence relevant to their claims and defenses. Rooted in the principle of fairness, discovery ensures both sides have access to the facts necessary to build their case. Its origins can be traced back to English common law, where discovery was initially a limited process reliant on written interrogatories and depositions to uncover the truth.

The modern concept of discovery took shape in the mid-20th century, particularly in the United States, with the adoption of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) in 1937. These rules expanded discovery tools, formalizing mechanisms such as depositions, requests for production, and interrogatories, which aimed to provide greater transparency and reduce surprises at trial. While there is a set period of time in each case in which discovery can be conducted, the length of discovery in a lawsuit can vary significantly, as it depends on the main sources of information that need to be presented and “discovered.”

Over time, the discovery process has undergone significant evolution, particularly with the advent of technology. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the proliferation of electronically stored information (ESI) transformed discovery, giving rise to the field of electronic discovery, or ediscovery. Courts and litigants were challenged to adapt traditional discovery practices to handle vast amounts of digital data, including emails, social media, and cloud-based information.

Case law rulings began to define requirements for parties in litigation to enforce their discovery obligations to the handling of electronic evidence. The Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM) was developed in 2005, and standardized the definition of the phases, processes, and workflows of ESI in ediscovery to support litigation needs.

Amendments to the FRCP in 2006 and 2015 have further reflected a shift toward ediscovery, emphasizing proportionality, collaboration, and the need to address the unique challenges of managing ESI.

In the modern era, technology continues to drive innovation in discovery, with advanced capabilities like cloud-based technology facilitating collaboration and automation, and tools like artificial intelligence and machine learning enabling faster, more efficient review and analysis of data. Despite these advancements, the discovery phase remains a dynamic and often contentious part of litigation, requiring a careful balance between thoroughness, cost-efficiency, and the protection of privacy and privilege.

Ediscovery: Not Just for Litigation Anymore

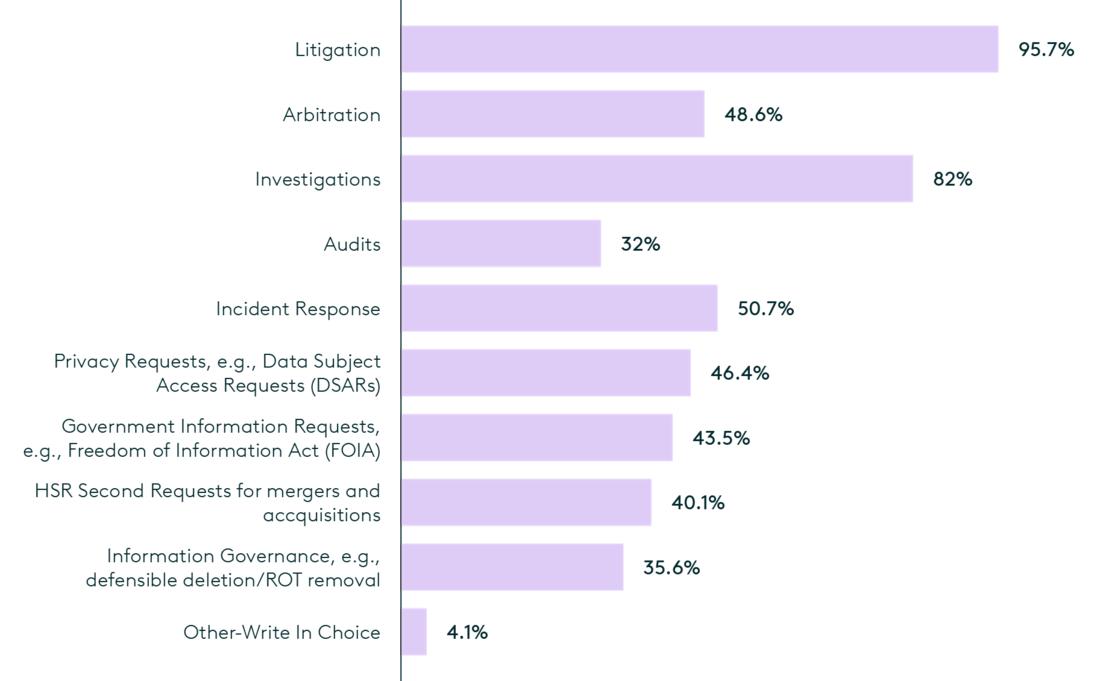

Over the years, ediscovery has expanded beyond traditional litigation to areas such as regulatory investigations, internal audits, data privacy compliance (e.g., with the General Data Protection Regulation and other data privacy laws), and cybersecurity incident response. Many of these don’t involve legal proceedings, so that succinct definition of ediscovery no longer applies. Today, many organizations apply ediscovery technology and workflows to several use cases other than litigation. In the 2024 State of the Industry report published by eDiscovery Today, at least 40% of 444 respondents said they apply ediscovery technology and workflows to seven different use cases!

15 Ediscovery Terms to Know

Like any discipline, an important key to understanding ediscovery is understanding the terms that relate to it. There are many terms that define the nuances and best practices associated with ediscovery, but some are vital to understanding what ediscovery is.

Electronically Stored Information (ESI)

As referenced in the U.S. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, information that is stored electronically, regardless of the media or whether it is in the original format in which it was created, as opposed to stored in hard copy (i.e., on paper).

Legal Hold

A communication issued as a result of current or reasonably anticipated litigation, audit, government investigation, or other such matter that suspends the normal disposition or processing of records.

Spoliation

The destruction of records or properties, such as metadata, that may be relevant to ongoing or anticipated litigation, government investigation, or audit.

Metadata

The generic term used to describe the structural in-formation of a file that contains data about the file, as opposed to describing the content of a file.

Record Custodian

An individual responsible for the physical storage of records throughout their retention period.

Document (or Document Family)

A collection of pages or files produced manually or by a software application, constituting a logical single communication of information, but consisting of more than a single stand-alone record. Examples include a fax cover, the faxed letter, and an attachment to the letter, the fax cover being the “Parent,” and the letter and attachment being a “Child.”

Native Format

Electronic documents have an associated file structure defined by the original creating application. This file structure is referred to as the native format of the document.

Load File

A file that relates to a set of scanned images or electronically processed files, and that indicates where individual pages or files belong together as documents, to include attachments, and where each document begins and ends. A load file may also contain data relevant to the individual documents, such as selected metadata, coded data, and extracted text.

De-duplication (de-dupe)

The process of comparing electronic files or records based on their characteristics and removing, suppressing, or marking exact duplicate files or records within the data set for the purposes of minimizing the amount of data for review and production.

Boolean Search

Boolean searches use keywords and logical operators such as “and,” “or,” and “not” to include or exclude terms from a search, and thus produce broader or narrower search results.

Early Data Assessment (EDA)

The process of separating possibly relevant electronically stored information from nonrelevant electronically stored information using both computer techniques, such as date filtering or advanced analytics, and human-assisted logical determinations at the beginning of a case. This process may be used to reduce the volume of data collected for processing and review. This process is also referred to as Early Case Assessment (ECA).

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

A subfield of computer science focused on the development of intelligence in machines so that the machines can react and adapt to their environment and the unknown. AI is the capability of a device to perform functions that are normally associated with human intelligence, such as reasoning and optimization through experience.

Machine Learning

A subset of artificial intelligence enabling a system to automatically improve at a task on its own based upon experience and data, without being explicitly programmed for that task.

Natural Language Search

A manner of searching that permits the use of plain language without special connectors or precise terminology, such as “Where can I find information on William Shakespeare?” as opposed to formulating a search statement, such as “information” and “William Shakespeare.”

Technology-Assisted Review (TAR)

A process for prioritizing or coding a collection of ESI using a computerized system that harnesses human judgments of subject-matter experts on a smaller set of documents and then extrapolates those judgments to the remaining documents in the collection. Also referred to as predictive coding.

Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM)

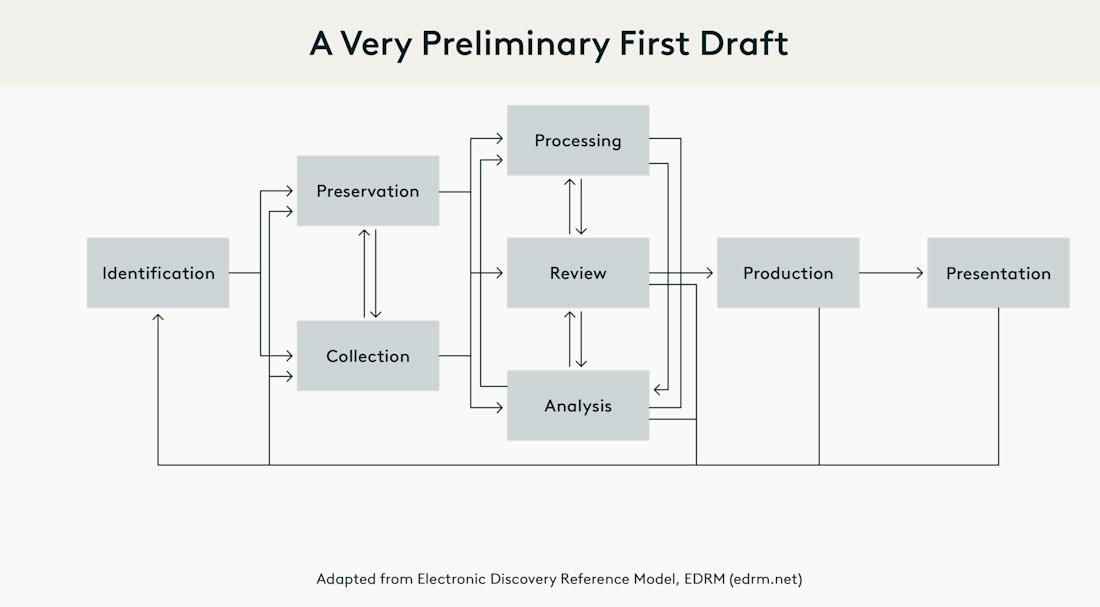

In 2005, George Socha and Tom Gelbmann gathered a group of nearly 40 ediscovery practitioners to construct an electronic discovery reference model that would provide definitions and a formal structure for describing the concepts and relationships in the electronic discovery processes. The earliest EDRM model containing eight phases looked like this:

Those eight phases can be defined as follows:

Identification. Locating potential sources of ESI and determining the scope, breadth and depth of that ESI.

Preservation. Ensuring that ESI is protected against inappropriate alteration or destruction.

Collection. Gathering ESI for further use in the ediscovery process.

Processing. Reducing volume of ESI and converting it to forms suitable for review and analysis.

Review. Evaluating ESI for relevance and privilege.

Analysis. Evaluating ESI for content and context, including key patterns, topics, people and discussion.

Production. Delivering ESI to others in appropriate forms and using appropriate delivery mechanisms.

Presentation. Displaying ESI before audiences (at depositions, hearings, trials, etc.) to elicit further information, validate existing facts or positions, or persuade an audience.

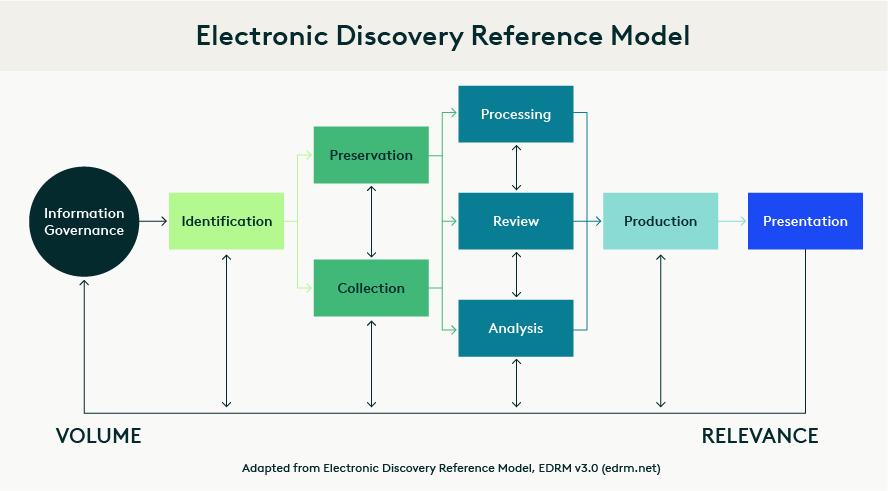

Over the years, the look of the EDRM model has changed. But only two substantial changes were applied to the model. The first was that the steps to litigation were replaced by shading that was applied to the bottom of the model to illustrate how the volume of ESI gets reduced during the lifecycle while the percentage of relevant ESI rises as non-relevant ESI is culled out.

The other notable change is the addition of a ninth phase at the beginning of the cycle. That phase was initially titled “Records Management” when the first official version of the model was released, then changed to “Information Management” in 2009, then changed again to “Information Governance” in 2014 – represented as a circle to illustrate that information governance is perpetual and not part of the linear process as the other eight phases.

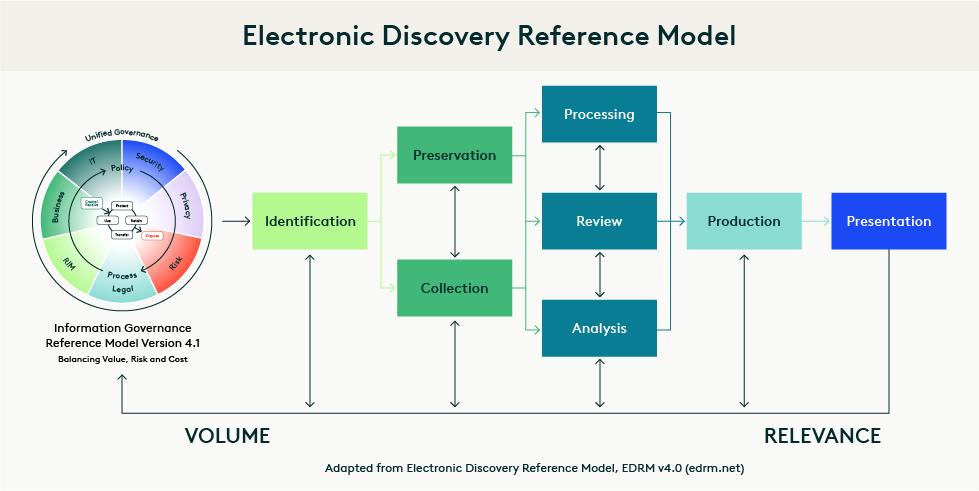

In March 2023, EDRM updated the look of the EDRM model with a new color scheme and also replaced the Information Governance circle with the Information Governance Reference Model (IGRM, which is also published by EDRM). At that time, EDRM also announced the EDRM 2.0 project, which is the first project since the original EDRM model was published in 2005 to consider changes to the core model itself.

Notable Rules Guiding Ediscovery

In addition to the EDRM model and notable case law rulings that have shaped how ediscovery is conducted, there have been amendments to FRCP rules over nearly two decades that were specifically designed to address discovery of ESI.

2006 Amendments to the FRCP

The 2006 amendments to the FRCP were pivotal in formally addressing the challenges posed by ESI in litigation. These amendments recognized the growing reliance on digital data and established rules to guide its discovery, balancing the need for access to relevant information with the practical challenges of handling large volumes of electronic data. Key highlights of these amendments include:

Rule 16 (Pretrial Conferences): The amendments encouraged courts and parties to address ediscovery early in the case. Rule 16 authorized pretrial scheduling orders to include provisions for managing ESI, such as preservation, scope, and privilege issues. This proactive approach aimed to reduce disputes and streamline discovery.

Rule 26(b)(2) (Proportionality and Limitations): This rule introduced proportionality considerations specific to ediscovery, emphasizing that discovery should be limited when the burden or cost of accessing ESI outweighs its potential benefit. It also addressed situations where ESI was "not reasonably accessible" due to undue burden or cost, allowing courts to limit discovery unless the requesting party demonstrated good cause.

Rule 26(f) (Meet and Confer Requirements): The amendments required parties to discuss ESI issues during their Rule 26(f) meet-and-confer sessions. Topics included the scope of ESI discovery, preservation obligations, the form of production, and potential privilege concerns. This collaboration aimed to preempt disputes over ESI.

Rule 33 (Interrogatories): This rule was updated to clarify that interrogatory answers may involve referencing ESI. If answering an interrogatory required significant data analysis, parties could provide access to relevant ESI for the requesting party to examine directly.

Rule 34 (Producing ESI): Rule 34 explicitly included ESI as discoverable material and allowed requesting parties to specify the desired form of production (e.g., native files or PDFs). Responding parties could object to the requested format, but they were required to produce ESI in a "reasonably usable" form.

Rule 37 (Safe Harbor for ESI Loss): This rule introduced a "safe harbor" provision to protect parties from sanctions for failing to produce ESI lost as a result of the "routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system." This provision acknowledged the challenges of preserving vast amounts of ESI, particularly when systems automatically overwrite or delete data.

At the time, these changes reflected a growing awareness of the complexities associated with digital information, from its sheer volume to the technical challenges of retrieval and preservation. By codifying specific rules for ediscovery, the amendments provided guidance for litigants and courts while also laying the groundwork for future refinements as technology continued to evolve.

2015 Amendments to the FRCP

The 2015 amendments to the FRCP further refined the discovery process to address challenges associated with ESI, particularly focusing on proportionality, cooperation, and the consequences of failing to preserve ESI. These amendments, built on the 2006 rules, respond to growing concerns about the cost and complexity of ediscovery. Key changes included:

Rule 1 (Cooperation): The 2015 amendments emphasized cooperation between parties in managing discovery. Rule 1 was revised to clarify that the FRCP "should be construed, administered, and employed by the court and the parties to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding." This signaled an expectation that litigants would work collaboratively to streamline discovery and avoid unnecessary disputes.

Rule 16 (Case Management): Rule 16 was updated to encourage courts to address ESI issues early in the litigation process, such as preservation obligations, potential privilege disputes, and the form of production. Courts were also encouraged to include ESI-related provisions in scheduling orders.

Rule 26(b)(1) (Scope of Discovery and Proportionality): The amendments explicitly redefined the scope of discovery to emphasize proportionality. Discovery was limited to information that is both relevant to a party’s claims or defenses and proportional to the needs of the case. Proportionality factors (moved up from Rule 26(b)(2)(b) in the 2006 amendments) included the importance of the issues at stake, the amount in controversy, the parties’ resources, and the burden or expense of discovery versus its likely benefit. This change sought to reduce overly broad or excessive discovery demands and to ensure that discovery efforts were tailored to the specific needs of the case.

Rule 34 (Specificity in Objections): Rule 34 was revised to require parties responding to requests for production to state with specificity any objections. Additionally, responding parties had to specify whether responsive documents or ESI were being withheld on the basis of those objections. This change aimed to improve transparency and reduce confusion about what was being produced.

Rule 37(e) (Failure to Preserve ESI): Perhaps the most notable change in the 2015 amendments, Rule 37(e) was revamped to address the consequences of failing to preserve ESI. The new rule established a uniform framework for courts to evaluate when sanctions are appropriate, replacing inconsistent approaches previously applied across jurisdictions. It distinguished between two scenarios – 1) If ESI is lost but no prejudice to the opposing party occurs, no sanctions are imposed, and 2) If ESI is lost and prejudice occurs, the court may impose measures to cure the harm, BUT there must be intent to deprive the party of ESI for the court to impose severe sanctions, such as adverse inference instructions, dismissal of claims, or entry of default judgment.

These changes sought to modernize discovery practices and address concerns about the escalating cost and burden of ediscovery. By emphasizing proportionality and cooperation, the amendments encouraged parties to engage in targeted discovery and focus on resolving cases efficiently. Together with the 2006 amendments, these updates reflected a shift toward balancing the need for relevant information with the realities of managing large volumes of ESI in litigation.

Important Rules to Know for Ediscovery

There are several rules that can apply to ediscovery disputes, but there are certain rules that typically drive most of the disputes over ediscovery. Here are the specific rules with links to the rule text:

Rule 26(b)(1) Proportionality: Known as the “six-factor test”, this rule has become common in disputes over the scope of discovery. The text reads:

Unless otherwise limited by court order, the scope of discovery is as follows: Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case, considering the 1) importance of the issues at stake in the action, 2) the amount in controversy, 3) the parties’ relative access to relevant information, 4) the parties’ resources, 5) the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and 6) whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable.

Rule 26(f)(3) Conference of the Parties and Discovery Plan: Known as the “Meet and Confer” rule, this rule establishes the expectation that the parties will meet and confer regarding the handling of ESI in Ediscovery. Failure to do so causes many courts to revert the dispute back to the parties to meet and confer to try to resolve the dispute before the court will get involved.

A discovery plan must state the parties’ views and proposals on:

(A) what changes should be made in the timing, form, or requirement for disclosures…;

(B) the subjects on which discovery may be needed, when discovery should be completed, and whether discovery should be conducted in phases or be limited to or focused on particular issues;

(C) any issues about disclosure, discovery, or preservation of electronically stored information, including the form or forms in which it should be produced;

(D) any issues about claims of privilege or of protection as trial-preparation materials..;

(E) what changes should be made in the limitations on discovery imposed under these rules or by local rule, and what other limitations should be imposed; and

(F) any other orders that the court should issue under Rule 26(c) or under Rule 16(b) and (c).

Rule 34(b)(1)(C) and 34(b)(2)(E) Form of Production: These two subsections address expectations regarding form of production for both requesting and producing parties. There are often disputes on how ESI should be produced and what level of metadata should be included in the production. While production of images with load files have been the standard historically, requesting parties are beginning to request native files with metadata more frequently, which has led to an increase in disputes.

(1) Contents of the Request. The request:

(C) may specify the form or forms in which electronically stored information is to be produced.

(2) Responses and Objections.

(E) Producing the Documents or Electronically Stored Information. Unless otherwise stipulated or ordered by the court, these procedures apply to producing documents or electronically stored information:

(i) A party must produce documents as they are kept in the usual course of business or must organize and label them to correspond to the categories in the request;

(ii) If a request does not specify a form for producing electronically stored information, a party must produce it in a form or forms in which it is ordinarily maintained or in a reasonably usable form or forms; and

(iii) A party need not produce the same electronically stored information in more than one form.

Rule 34(b)(2) Objections: This rule directly addresses “boilerplate objections” (such as “overly broad and unduly burdensome”), which have been a traditional initial response to discovery requests. Now, in most instances, those objections are waived.

(B) Responding to Each Item. For each item or category, the response must either state that inspection and related activities will be permitted as requested or state with specificity the grounds for objecting to the request, including the reasons. The responding party may state that it will produce copies of documents or of electronically stored information instead of permitting inspection. The production must then be completed no later than the time for inspection specified in the request or another reasonable time specified in the response.

(C) Objections. An objection must state whether any responsive materials are being withheld on the basis of that objection. An objection to part of a request must specify the part and permit inspection of the rest.

Rule 37(e) Spoliation and Sanctions: This rule addresses the sanctions for spoliation of ESI based on whether the requesting party was prejudiced by the spoliation and whether there was intent to deprive that party by the producing party. Many discovery disputes involve requests for sanctions over ESI spoliation.

(e) Failure to Preserve Electronically Stored Information. If electronically stored information that should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation is lost because a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and it cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery, the court:

(1) upon finding prejudice to another party from loss of the information, may order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice; or

(2) only upon finding that the party acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information’s use in the litigation may:

(A) presume that the lost information was unfavorable to the party;

(B) instruct the jury that it may or must presume the information was unfavorable to the party; or

(C) dismiss the action or enter a default judgment.

Additionally, there is one rule in the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) that is frequently involved in disputes regarding attorney-client and work product privilege and waiver of that privilege when there is disclosure of privileged information.

Rule 502 Limitations on Waiver of Privilege: Rule 502(b) discusses the conditions under which an inadvertent disclosure of privileged information doesn’t operate as a waiver, but all three conditions must be met. Getting a Rule 502(d) order means that any disclosure of privileged information doesn’t operate as a waiver in the current case or any subsequent Federal or State case, even if you haven’t taken reasonable steps to prevent the disclosure. You should always request a 502(d) order in Federal cases.

(b) Inadvertent Disclosure. When made in a federal proceeding or to a federal office or agency, the disclosure does not operate as a waiver in a federal or state proceeding if:

(1) the disclosure is inadvertent;

(2) the holder of the privilege or protection took reasonable steps to prevent disclosure; and

(3) the holder promptly took reasonable steps to rectify the error, including (if applicable) following Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26 (b)(5)(B).

(d) Controlling Effect of a Court Order. A federal court may order that the privilege or protection is not waived by disclosure connected with the litigation pending before the court — in which event the disclosure is also not a waiver in any other federal or state proceeding.

Case Law Rulings That Have Shaped Ediscovery

There have been several cases over the years that have shaped how ediscovery is conducted. Here are ten notable case law rulings that have shaped ediscovery practices over the years.

Zubulake v. UBS Warburg

This series of landmark rulings between 2003 and 2004 were pivotal in shaping modern ediscovery practices and standards. These rulings emphasized the obligation of parties to preserve and produce ESI during litigation. In particular, the court clarified the scope of a party's duty to preserve evidence once litigation is reasonably anticipated, extending this duty to relevant emails, backups, and other forms of digital communication. New York Judge Shira Scheindlin's rulings also defined the balance of cost-shifting in ediscovery, holding that while producing parties generally bear the costs of ESI production, courts could shift costs to the requesting party under certain circumstances, especially when requests are deemed excessively burdensome or expensive.

The Pension Committee of the Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities, LLC, (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 15, 2010)

In this case, New York Judge Shira Scheindlin defined negligence, gross negligence, and willfulness from an ediscovery standpoint. Finding gross negligence on the part of 13 plaintiffs, Judge Scheindlin sanctioned them based on their alleged failure to timely issue written litigation holds and to preserve certain evidence before the filing of the complaint.

Da Silva Moore v. Publicis Groupe & MSL Group, No. 11 Civ. 1279 (ALC) (AJP) (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 24, 2012)

This historic ruling by New York Judge Andrew J. Peck was the first case in which a Court approved of the use of computer-assisted review. Today, the use of TAR has become common, especially in cases involving large ESI collections.

Nuvasive, Inc. v. Madsen Med. Inc., No. 13cv2077 BTM(RBB) (S.D. Cal. Jan. 26, 2016)

In this case, the Court granted the motion for an order vacating the motion for sanctions for spoliation of evidence, citing the amendment of FRCP Rule 37(e) since the sanctions motion had been granted, which required a finding of intent to deprive for an adverse inference sanction. This case illustrates how sanctions for spoliation of evidence are treated before and after the 2015 rules amendments.

Hyles v. New York City, No. 10 Civ. 3119 (AT)(AJP) (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 1, 2016)

Citing Sedona Principle 6 (“Responding parties are best situated to evaluate the procedures, methodologies, and technologies appropriate for preserving and producing their own electronically stored information.”), New York Judge Andrew J. Peck refused to order the defendant to use TAR against their wishes.

Williams v. Angie’s List, No. 1:16-00878-WTL-MJD (S.D. Ind. April 10, 2017)

Here, the Court determined that the plaintiffs’ request for production of data from Salesforce was within Angie's List's "possession, custody, or control" under Rule 34(a), signifying that cloud-based repositories for an organization are still the responsibility of that organization in discovery.

Bellamy v. Wal-Mart Stores, Texas, LLC, No. SA-18-CV-60-XR (W.D. Tex. Aug. 19, 2019)

Texas Judge Xavier Rodriguez, using FRE 502(b) (as there was no Rule 502(d) order), ruled the defendant was entitled to "claw back" the documents it inadvertently produced. However, he did grant the plaintiff's request for sanctions based on the information in those documents. This case shows the importance of minimizing the risk of inadvertent disclosures and having a 502(d) order.

Benebone v. Pet Qwerks, et al., No. 8:20-cv-00850-AB-AFMx (C.D. Cal. Feb. 18, 2021)

The Court, in granting the defendants’ motion to compel production of Slack communications responsive to their document requests, found that “requiring review and production of Slack messages by Benebone is generally comparable to requiring search and production of emails and is not unduly burdensome or disproportional to the needs of this case – if the requests and searches are appropriately limited and focused.” This was the first significant ruling involving the discoverability of data from collaboration apps like Slack.

Rossbach v. Montefiore Med. Ctr., No. 19cv5758 (DLC) (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 5, 2021)

In this case, New York Judge Denise Cote granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss the case after it was determined that the plaintiff fabricated a text message exchange between her and the supervisor she accused of sexual harassment. Key to the determination that the text message exchange was fabricated was the use of an emoji that was impossible with the plaintiff’s version of iOS on her iPhone. This case demonstrates the importance of evidence authentication and the rise of emojis in electronic evidence.

Nichols, et al. v. Noom Inc., et al. No. 20-CV-3677 (LGS) (KHP) (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 11, 2021)

In this case, New York Judge Katherine Parker denied the plaintiffs’ motion for reconsideration on whether the defendant must reproduce hyperlinked files as “attachments” to the emails in Gmail that were produced, finding that the issue wasn’t specifically addressed in the parties’ ESI protocol. This case is the first significant ruling in the debate of whether hyperlinked files should be treated as “modern attachments” and it illustrates the importance of addressing these considerations before agreeing to an ESI protocol.