Social Media Data in Ediscovery

Social media is huge – and its popularity continues to grow.

In 2005, when the Pew Research Center began tracking adoption, only 5% of American adults used at least one social media platform. By 2011, half of all Americans used social media, and in 2021, the share was 72%.

On the world stage, in 2024 there were 5.07 billion social media users, accounting for 62.6% of the total global population. That number is projected to reach almost 8 billion in 2027.

The numbers illustrate the popularity of social media sites around the world (as of May 2023):

Facebook had 2.9 billion monthly active users.

Instagram had 1.6 billion users.

TikTok reportedly had 1.09 billion users aged 18 and above.

Twitter, now known as X, had 372.9 million users.

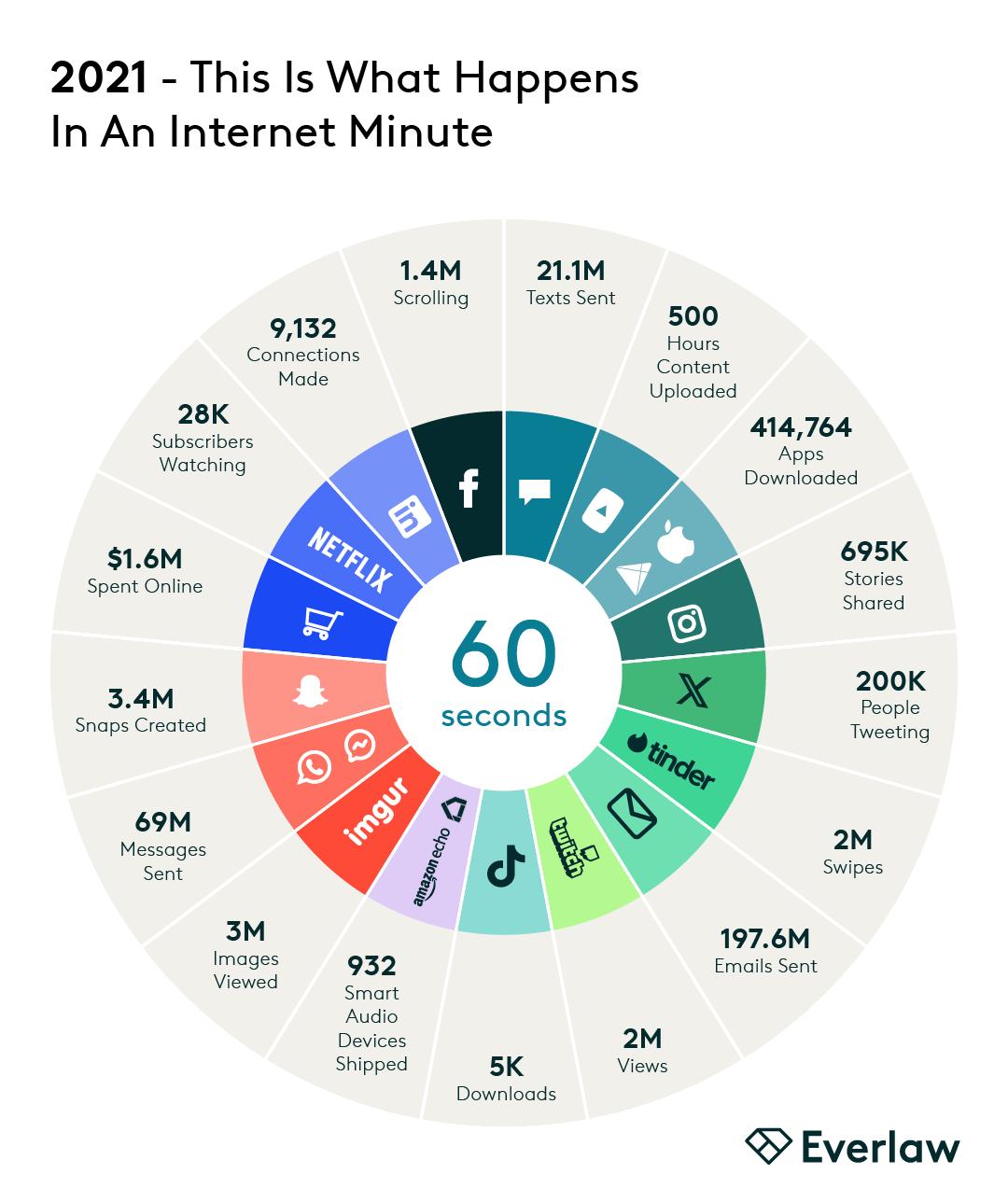

An incredible volume of information is now being exchanged openly on these platforms – from photographs and video to location markers and even communications – all at lightning speed, every minute of the day. The infographic below illustrates what happens in an average minute on the internet every day, including for social media sites like Facebook, X, Instagram, and TikTok:

Due to its spontaneity, relative permanence, and easy accessibility, data from social media is quickly becoming a burgeoning source of evidence for legal proceedings. What once might have been kept private may not only be more publicly available but also discoverable in litigation and investigations. It’s crucial to understand when social media evidence is relevant to investigations and litigation, the common discovery challenges it raises, some best practices for handling it in discovery, how to collect it from different social media platforms, and how case law precedent can guide discovery of social media evidence.

When Is Social Media Evidence Relevant to Investigations and Litigation?

The use of social media evidence in litigation and investigations has become commonplace. Courts have allowed discovery of social media evidence when litigants can show its relevance to the case, and that evidence could conceivably apply to any case.

Typical Cases Where Social Media Evidence Is Particularly Relevant

However, there are certain types of legal matters where social media may be particularly relevant:

Product liability and personal injury. Activity on social media accounts can confirm or refute health and injury claims by showing the activities of the plaintiff(s) in the case.

Divorce and custody disputes. Social media account activity can be used to disclose assets that a party has tried to hide or to show that an individual as being unfit for parenting.

Employment investigations. Social media activity can serve as evidence of everything from claims of a hostile work environment to supporting evidence of employee misconduct (e.g., out at an event during a “sick” day, possessing assets that could be the result of embezzlement, etc.).

Libel cases. Social media evidence can be included as part of the basis for a libel case where one party claims the social media content of an individual or company is defamatory, false, and caused the claimant injury or damages.

Criminal cases. Social media evidence can illustrate evidence of a crime being committed or help exonerate a suspect when online activity corresponds to the timeline of an alleged crime that has occurred.

Regardless of the type of case, preservation of potentially responsive social media evidence from your custodians and discovery of it from the opposing party (or related third parties) should always be considered.

It’s important to have a set of standard social media preservation instructions that can be customized according to the needs of the case and included in the legal hold notice to potential custodians. It’s equally important to understand the discoverable form(s) of each social media platform and establish a standard set of interrogatories and discovery requests for each platform to maximize the value of the data being produced to you.

Laws Applicable to Social Media Litigation

A number of laws can apply to social media litigation in terms of discovery and relevance of social media evidence:

The Stored Communications Act, orSCA, 18 U.S. Code section 2701 et seq., addresses voluntary and compelled disclosure of “stored wire and electronic communications and transactional records” held by third-party internet service providers, which includes social media platform providers such as Facebook, X, Instagram, and TikTok.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or DMCA, which updated U.S. copyright law in 1998 to address important parts of the relationship between copyright and the internet, including the establishment of protections for online service providers in certain situations if their users engage in copyright infringement.

The Communications Decency Act, or CDA, is the short name of Title V of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. It imposes criminal sanctions for knowingly transmitting obscene messages or materials over the internet under certain circumstances. Section 230 of the CDA gives providers and users of "interactive computer services" broad immunity from liability for third-party content transmitted via their services. Service providers are protected even if they have actual notice of the offensive content.

The Copyright Act of 1976 forms the basis of copyright law in the United States today. Copyright protection extends to all “original works of authorship” and to new kinds of media. However, the fair use doctrine of U.S. copyright law allows the use of limited portions of a work, such as quotes, for criticism, commentary, news reporting, and scholarly reports.

Common Challenges with Social Media Evidence

Ediscovery of social media evidence can be difficult. Challenges that organizations are likely to encounter include accessing social media data of custodians, maintaining the chain of custody during preservation and collection, reviewing social media evidence in a form consistent with how it appears on the social media platform, and producing social media data to opposing counsel. It’s also important to be able to authenticate social media evidence to ensure that the evidence being presented is what it purports to be.

Access

More than 100 popular social media platforms are in use today. Navigating the complex web of a custodian’s social media presence during ediscovery can be challenging. Identifying forgotten platforms and abandoned profiles and compiling a comprehensive list of the accounts in use requires a thorough and detailed custodian-interview process. It’s also a good idea to conduct your own investigation of the custodian’s social media footprint to identify accounts that the custodian may have forgotten or doesn’t want to disclose. It’s essential to pinpoint any social media data sources up front rather than be surprised by the disclosure of them during legal proceedings (such as during a deposition) later.

In addition to public information – such as profiles, pictures, and posts – you may need to request permission to access private accounts and communications. Regardless of the data type, accessing the social media archive of a custodian typically requires cooperation from the custodian, either through a managed self-collection process or by obtaining their credentials so that your team can access the data. Many custodians will raise privacy concerns, so it’s important to be able to demonstrate the likely relevance of the data to the court to overcome those concerns and compel the custodian to produce the data.

Preservation and Collection

There are several ways to preserve and collect social media evidence, and you need to consider potential requirements to authenticate the evidence downstream. Taking a screenshot or downloading a PDF to document social media evidence is a common approach to preservation and collection, and it may be necessary if there are concerns that the custodian might delete the evidence. However, that method may lack key metadata, which aids in discovery and authentication of the evidence, so it’s important to have a plan for demonstrating chain of custody and authenticating any social media evidence collected through these methods.

Another challenge is hyperlinked data. Social media posts often contain links to other data sources (such as other social media posts, articles, YouTube videos, etc.), and that content may be as important as the post itself. Unless the collection process includes extending out to these other data sources, there is no guarantee that the linked data source will still be there later.

Data can also be downloaded in different forms. Many social media platforms support downloading social media data in either HTML or JSON format. HTML may be more usable natively, but JSON may be better supported for uploading into your review platform.

It’s vital to understand the options for preserving and collecting social media evidence so that you can meet your discovery obligations if you’re producing the data or seek the most useful form of production if you’re requesting it.

Review and Production

Reviewing social media evidence can bring up two issues:

1. The format in which the data is presented for review.

2. The potential volume of data to review, especially for a custodian who is an active user of social media.

The format in which the data is being reviewed is important as it needs to be presented in a manner that approximates how the data is viewed within the social media platform. This can be tricky, as each platform provides a distinct approach and interface. For example, the interface for Instagram is optimized for mobile, so in review, Instagram data will often look different.

Defining a “document” for review within social media data can be complicated as well. Some social media collection tools capture an entire social media account as a single page instead of breaking it up into smaller components (such as each post as a separate document). That makes it difficult to effectively cull the data to minimize review time.

Given that many social media consumers use their preferred platforms daily (sometimes with multiple posts, likes, comments, emojis, pictures, and/or videos each day), the volume of data to be reviewed can be extensive. The ability to cull the data prior to review may be hampered by the format in two ways:

1. How a “document” is defined (as discussed above).

2. The size of the “document.”

Many posts and comments may be as small as just a few words, a link to a separate site, or even an emoji, making it difficult to apply search terms or technology assisted review, or TAR, approaches to identify potentially responsive social media content.

The form in which social media evidence is produced can vary widely, depending on the needs of the case. Parties often agree to convert social media content to PDF files for production, but that eliminates metadata that may provide additional useful information or may be important to aid in authenticating the evidence.

Rule 901 of the Federal Rules of Evidence provides an expectation that “the proponent must produce evidence sufficient to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it is” to satisfy the requirement of authenticating the item of evidence in question. The ability to provide metadata can support the authentication example found in Rule 901(b)(4): “Distinctive Characteristics and the Like. The appearance, contents, substance, internal patterns, or other distinctive characteristics of the item, taken together with all the circumstances.”

If the metadata is unavailable or not produced, you may need to authenticate the evidence via testimony, as discussed in Rule 901(b)(1): “Testimony of a Witness with Knowledge. Testimony that an item is what it is claimed to be.” No matter how social media evidence is produced, a plan must be in place for how to authenticate that evidence.

Best Practices: Seven Rules for Handling Social Media in Discovery

You can significantly increase your level of success by keeping in mind a few tried-and-true approaches – including around legal holds, privacy matters, and evidence authentication. Here are seven tips to help ensure a smooth and productive discovery process for social media data:

Issue a hold notice promptly. As is the case with any other forms of evidence, potential custodians must be notified promptly not to delete potentially responsive social media content. This notice should be detailed enough to address custodian responsibilities with regard to their duty to preserve and issued when litigation is anticipated. You don’t want to find out later that your client has “cleaned up” their social media page to remove documented activity that may damage their case.

Interview and investigate. Conduct a detailed interview of any potential custodians to identify what social media platforms they use, how long they’ve been using each platform, frequency of access, etc. Consider having your team conduct its own investigation to determine the social media footprint of your custodians. Always investigate to determine the social media footprint of potential opponent custodians and third parties likely to have relevant data. Much of their social media activity may be publicly available.

Account for privacy considerations. As your opponents may conduct their own investigations of your custodians, discuss with them privacy settings on their own social media pages and the implications of each privacy setting. Be prepared to demonstrate the potential relevance of social media evidence for opponent and third-party custodians in the event they raise privacy objections to production requests.

Meet and confer on social media discovery requirements. It’s best to get any potential disagreements with opposing counsel on the table early so that they can be addressed promptly. In many cases, you may be able to obtain and document agreement that social media is unlikely to provide data relevant to the case. When social media evidence is expected to be relevant, try to agree on the form of production so that you know what steps you must take to produce the data or what format you should expect to receive to maximize the value of the evidence to you.

Manage preservation and collection. When preserving and collecting a custodian’s social media archive, that custodian will likely need to be involved – either to collect the data themselves or to provide their credentials for someone from your team to do so. Either way, it’s important to manage preservation and collection to ensure a guided process. Unsupervised self-collections often lead to problems later in discovery.

Understand the data alternatives. To streamline the discovery process, it’s necessary to understand the data alternatives so that you can choose the form of collection, review, and production that best fits your case. In many cases, there will be minimal relevant social media data, so capturing screenshots or printing to PDF may be sufficient (assuming you can support with testimony to authenticate, if needed). In cases where an extensive review of a custodian’s social media archive is required, the choice to download as HTML or JSON data may depend on the capabilities of your review platform to ingest the data to support review.

Have a game plan for authentication. Understand that you will need to authenticate any social media evidence you plan to present, including testimony and/or metadata. Authentication requirements often dictate the manner in which you preserve, collect, produce, and present social media evidence.

Collecting Social Media Evidence

It would be difficult to represent the more than 100 social media platforms here. For this guide, we have chosen four popular platforms as examples of how to request and collect data from them.

For each example, we provide resources and links* to illustrate three aspects of collecting data from a social media platform:

1. The terms of service or terms of use of the platform.

2. The process for handling requests from law enforcement.

3. How to download data from the platform.

Most platforms will provide resources for all three considerations.

Terms of service. Facebook’s Terms of Service discuss the services that Facebook provides, how those services are funded, guidelines for using Facebook, other provisions (including account suspension or termination, limits on liability, and handling of disputes), and other terms and policies (including ad controls, as well as privacy, cookie, and data policies).

Law enforcement requests. Meta Platforms, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, provides operational guidelines for law enforcement officials seeking records, including U.S. legal requirements (which include a valid subpoena or court order, pursuant to the SCA) and international legal requirements.

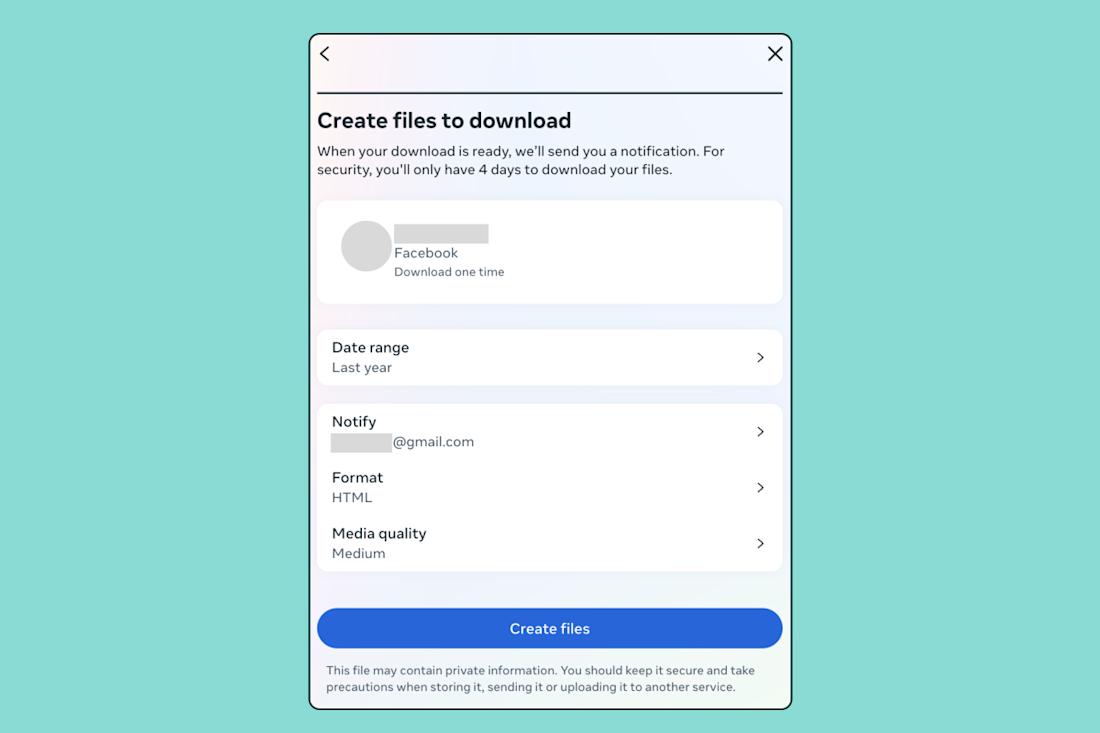

Collecting data. Facebook allows you to download your information. The data are available in HTML or JSON format. HTML downloads are delivered in a ZIP file that contains an HTML file named Index that you can open in a web browser. In the ZIP file are folders with files that include any images and videos you’ve requested. JSON format is machine readable and facilitates transfer of data to another platform (assuming it has built an ingestion capability of the JSON data).

Per the Facebook FAQ, the categories of data that can be downloaded include the following:

Your activity across Facebook. Information and activity from different areas of Facebook, such as posts you created, photos you’re tagged in, groups you belong to, and more.

Personal information. Information you provided when you set up your Facebook accounts and profiles.

Connections. Who and how you’ve connected with people on Facebook, including your friends and followers.

Logged information. Information that Facebook logs about your activity, including your location history and search history.

Security and login information. Technical information and logged activity related to the account.

Apps and websites off Facebook. Apps you own and activity received from apps and websites off Facebook.

Preferences. Actions you’ve taken to customize your experience on Facebook.

Ad information. Your interactions with ads and advertisers on Facebook.

As described in a blog post by X1, available Facebook metadata fields include the following:

Metadata Field | Description |

uri | Unified resource identifier of the subject item |

fb_item_type | Identifies item as Wallitem, Newsitem, Photo, etc. |

parent_itemnum | Parent item number-sub item are tracked to parent |

thread_id | Unique identifier of a message thread |

recipients | All recipients of a message listed by name |

recipients_id | All recipients of a message listed by user ID |

album_id | Unique ID number of a photo or video item |

post_id | Unique ID number of a wall post |

application | Application used to post to Facebook |

user_img | URL where user profile image is located |

user_id | Unique ID of the poster/author of a Facebook item |

account_id | Unique ID of a user’s account |

user_name | Display name of poster/author of a Facebook item |

created_time | When a post or message was created |

updated_time | When a post or message was revised/updated |

to | Name of user to whom a wall post is directed |

to_id | Unique ID of user to whom a wall post is directed |

link | URL of any included links |

comments_num | Number of comments to a post |

picture_url | URL where picture is located |

The Download Your Information form is shown below.

Terms of use. Instagram’s Terms of Use discuss the services that Instagram provides, how those services are funded, data policy, guidelines for using Instagram, additional Instagram rights, content removal and disabling/terminating accounts, and dispute resolution.

Law enforcement requests. The parent company of Facebook and Instagram (Meta Platforms) provides operational guidelines for law enforcement officials seeking records, including U.S. legal requirements (which include a valid subpoena or court order, pursuant to the SCA) and international legal requirements.

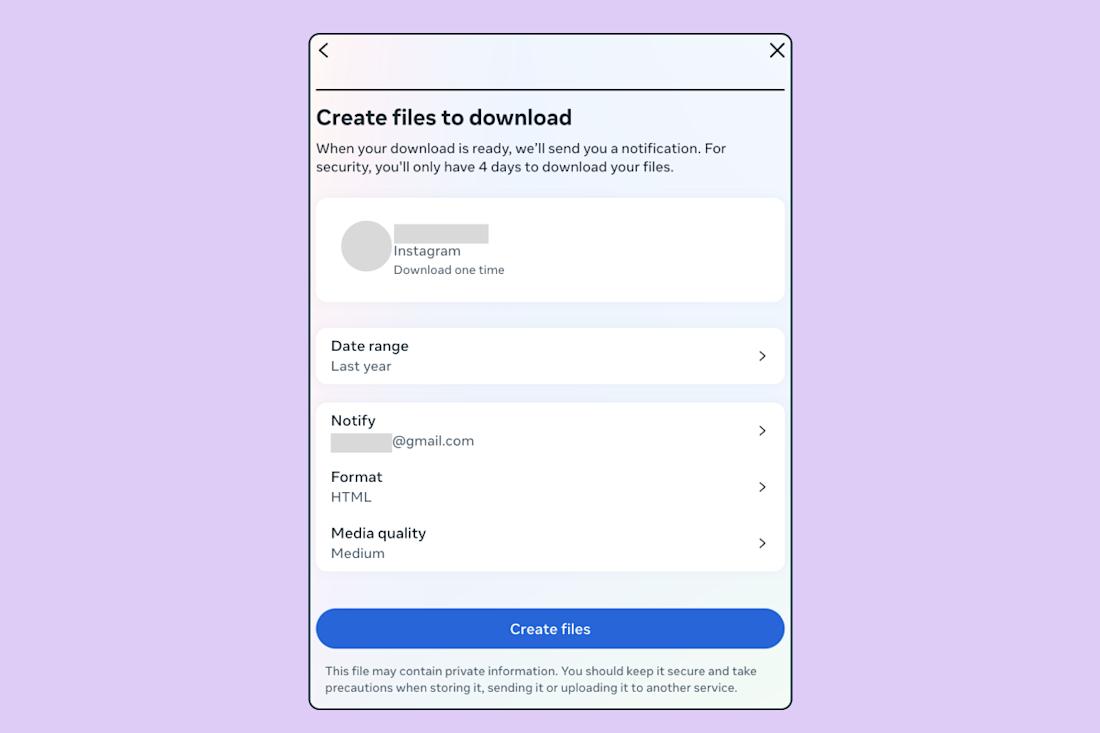

Collecting data. Instagram allows you to download your information in HTML or JSON format. Per Instagram: “It may take up to 30 days for us to email you a download link. Some data you have deleted may be stored temporarily for safety and security purposes, but will not appear when you access or download your data.”

The Download Your Information form is shown below.

X (Formerly Twitter)

Terms of service. X’s Terms of Service describe who may use X services, give a link to the privacy policy, set out responsibilities and rules for placing content on X and for using X services, and list disclaimers and limitations of liability.

Guidelines for law enforcement. X provides a page with law enforcement guidelines, including an explanation of the information that X stores, data retention information, preservation requests, and procedures for requesting account information (including a subpoena or court order, required for private information).

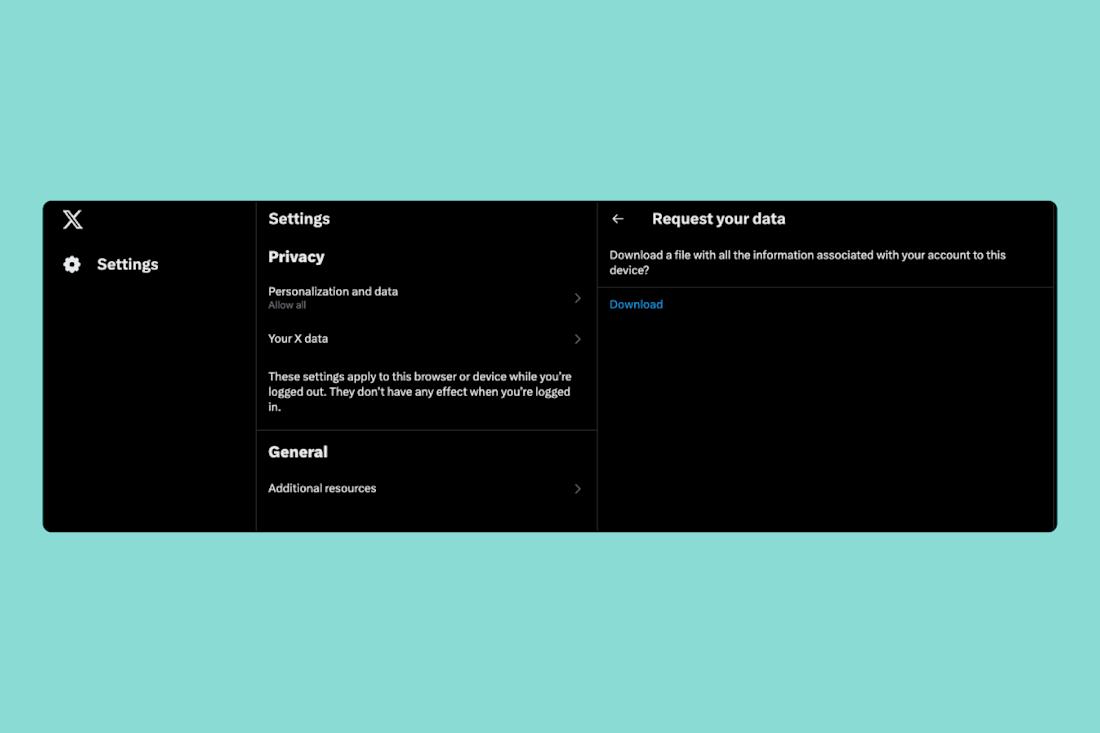

Collecting data. X allows you to request an archive (HTML only) that includes information such as the @handles of your followers and those you follow, your posts with links, your direct messages, your lists, and your profile in a clickable form. X states that “it can take 24 hours or longer for your data to be ready” and the link is active for seven days.

Available Xmetadata fields include the following:

Metadata Field | Description |

truncated | Indicates if a post has been automatically truncated |

user_id | Identity of the poster |

handle | Screen name |

retweet_user | Username of the user who reposted |

direct_message | Indicates if the post is a direct message |

coordinates | Global coordinates from where the post was sent |

The Request Archive form is shown below.

TikTok

Terms of service. TikTok’s Terms of Service discuss your relationship with TikTok, how using the services constitutes accepting the terms, the responsibilities and rights associated with your account and use of the services, intellectual property rights, rights and ownership of content, as well as indemnity, exclusion of warranties, and limitation of liability.

Law enforcement guidelines. TikTok’s law enforcement guidelines cover where to address requests, types of data subject to a law enforcement request, requirements when making a request (including requesting authority or court), notification of affected users, preservation requests, and the procedures for emergency requests.

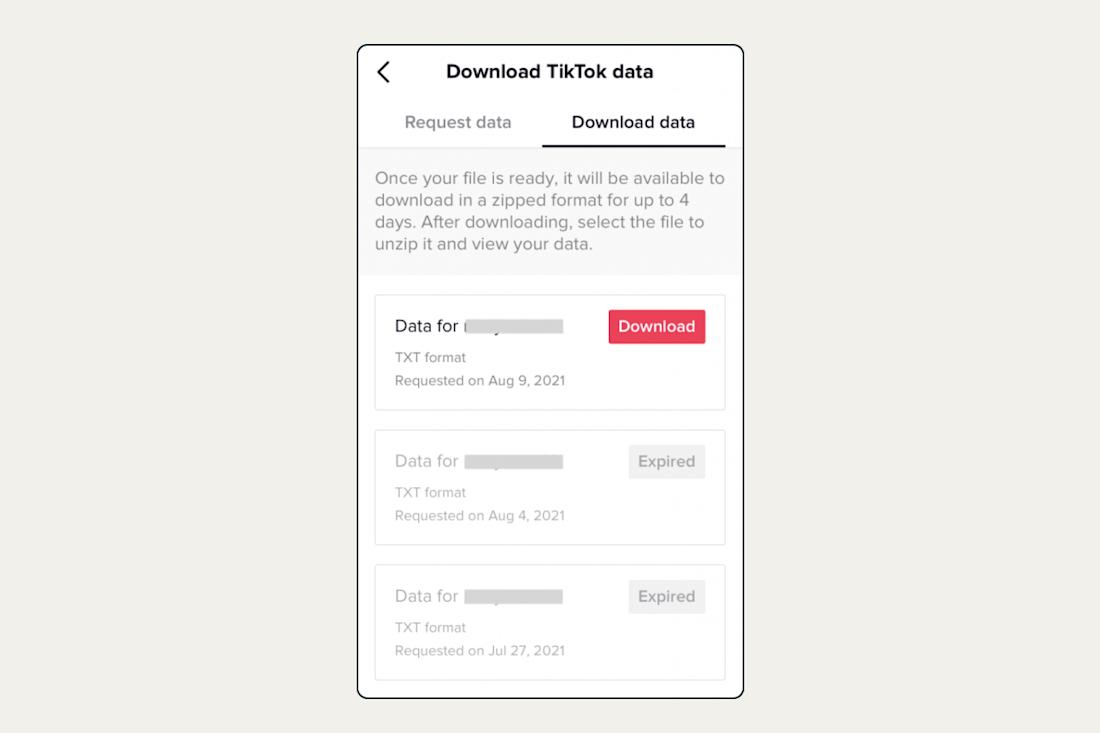

Collecting data. Users can request a copy of TikTok data, which can include your profile photo, description, and contact info; your activity (such as videos, chat, comment and purchase history, and favorites); and your app settings (for privacy, notifications, and language). TikTok discusses how to request your data here. It can take up to three days to prepare the ZIP file, and it will be available for up to four days.

Unfortunately, your TikToks are not automatically downloaded once you receive a copy of your data – you will have to open the data file and download each video manually.

The Download TikTok Data form is shown below.

*Disclaimer: Individual social media platform information is current as of publication date and may change over time. Please check directly with the social media providers for the latest.

Key Case Law Rulings Regarding Social Media Data in Ediscovery

Numerous case law rulings have come down over the years regarding evidence from social media platforms. Here are several notable cases involving social media data in ediscovery.

Lester v. Allied Concrete Co. (Va. Cir. Ct. September 6, 2011)

In this case, the plaintiff’s attorney was ordered to pay $542,000 for instructing his client to remove at least 15 photos from his Facebook page, including one of the plaintiff (who was a recent widower suing about the death of his wife) holding a beer and wearing a T-shirt that said “I ♥ hot moms.” The plaintiff was ordered to pay $180,000 for obeying the attorney’s instructions.

People v. Harris (N.Y.C. Crim. Ct., June 30, 2012)

In this case, the court ruled that Twitter must produce tweets and user information of the defendant, an Occupy Wall Street protester, who clashed with New York Police in October of 2011 and faced disorderly conduct charges, stating: “If you post a tweet, just like if you scream it out the window, there is no reasonable expectation of privacy. There is no proprietary interest in your tweets, which you have now gifted to the world. This is not the same as a private email, a private direct message, a private chat, or any of the other readily available ways to have a private conversation via the internet that now exist.… Those private dialogues would require a warrant based on probable cause in order to access the relevant information.”

EEOC v. Original Honeybaked Ham Co. of Georgia (D. Colo. November 7, 2012)

Here, the court stated: “There is a strong argument that storing such information on Facebook and making it accessible to others presents an even stronger case for production, at least as it concerns any privacy objection.” The court ruled that where a party had showed certain of its adversaries’ social media content and text messages were relevant, the adversaries must produce usernames and passwords for their social media accounts, usernames and passwords for email accounts and blogs, and cell phones used to send or receive text messages to be examined by a forensic expert as a special master in camera.

Shenwick v. Twitter, Inc. (N.D. Cal. February 7, 2018)

In this case, the court ruled on several discovery disputes between the parties, including denial of a request by the plaintiffs to order the defendants to produce protected direct messages of individual custodians, where the judge stated: “Plaintiffs merge Twitter and its individual custodians’ rights. They are not the same. If Plaintiffs issued a third party subpoena to a company—not Twitter—for direct messages that the individual custodians sent and received, there is no question that the Court could not enforce such a subpoena. Under the same reasoning, the Court cannot compel Twitter, a party in this litigation, to produce protected direct messages of individual custodians who are not parties simply because Twitter is also the provider of the direct messaging service.”

Forman v. Henkin (N.Y. February 13, 2018)

In this case, the Court of Appeals of New York reinstated a trial judge’s ruling requiring the plaintiff who was disabled in a horse-riding accident to turn over “private” photos to the defendant taken before and after her injuries, stating: “the Appellate Division erred in modifying Supreme Court’s order to further restrict disclosure of plaintiff’s Facebook account, limiting discovery to only those photographs plaintiff intended to introduce at trial. With respect to the items Supreme Court ordered to be disclosed (the only portion of the discovery request we may consider), defendant more than met his threshold burden of showing that plaintiff’s Facebook account was reasonably likely to yield relevant evidence.”

Vasquez-Santos v. Mathew (N.Y. App. Div. January 24, 2019)

Here, the New York Appellate Division, First Department panel “unanimously reversed” an order by the Supreme Court, New York County, in June 2018 that denied the defendant’s motion to compel access by a third-party data-mining company to plaintiff’s devices, email accounts, and social media accounts, so as to obtain photographs and other evidence of plaintiff engaging in physical activities, and granted the defendant’s motion, stating: “Although plaintiff testified that pictures depicting him playing basketball, which were posted on social media after the accident, were in games played before the accident, defendant is entitled to discovery to rebut such claims and defend against plaintiff's claims of injury. That plaintiff did not take the pictures himself is of no import. He was ‘tagged,’ thus allowing him access to them, and others were sent to his phone.”

Hampton v. Kink, et al. (S.D. Ill. January 13, 2021)

Here, the court granted the defendants’ motion to compel, ordering the plaintiff to produce to the defendants the name of her Facebook handle by January 20, and also granted the plaintiff’s motion to compel, ordering the defendants to produce relevant posts from a private Facebook page used by correctional staff.

Brown v. SSA Atlantic (S.D. Ga. March 16, 2021)

In this case, the court granted in part the defendant’s motion for spoliation sanctions against the plaintiff for his deactivated Facebook account and failing to disclose others, ordering the plaintiff to produce data from his Facebook account(s) and also directing the plaintiff and his attorney to show cause why sanctions should not be imposed, pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure’s 26(g) certification requirements.

Torgersen v. Siemens Bldg. Tech. et al. (N.D. Ill. May 24, 2021)

Here, the court granted the defendants’ motion to compel and for sanctions for the plaintiff’s intentional deletion of his Facebook account after he had a known duty to preserve ESI from that account, stating that “Plaintiff’s explanation for what happened here is balderdash.” But the court ruled that jury instructions (including an adverse inference instruction), rather than case dismissal, was the appropriate sanction.

State v. Jesenya O. (N.M. June 16, 2022)

In this case, the Supreme Court of New Mexico, considering an appeal relating to the authentication of social media evidence, found that the state’s authentication showing was sufficient under New Mexico Rule 11-901 to support a finding that, more likely than not, the Facebook Messenger account used to send the messages belonged to Jesenya O. (Child) and that Child was the author of the messages. So the court reversed the Court of Appeals and reinstated Child’s delinquency adjudications.

Download the court rulings in this chapter in PDF.